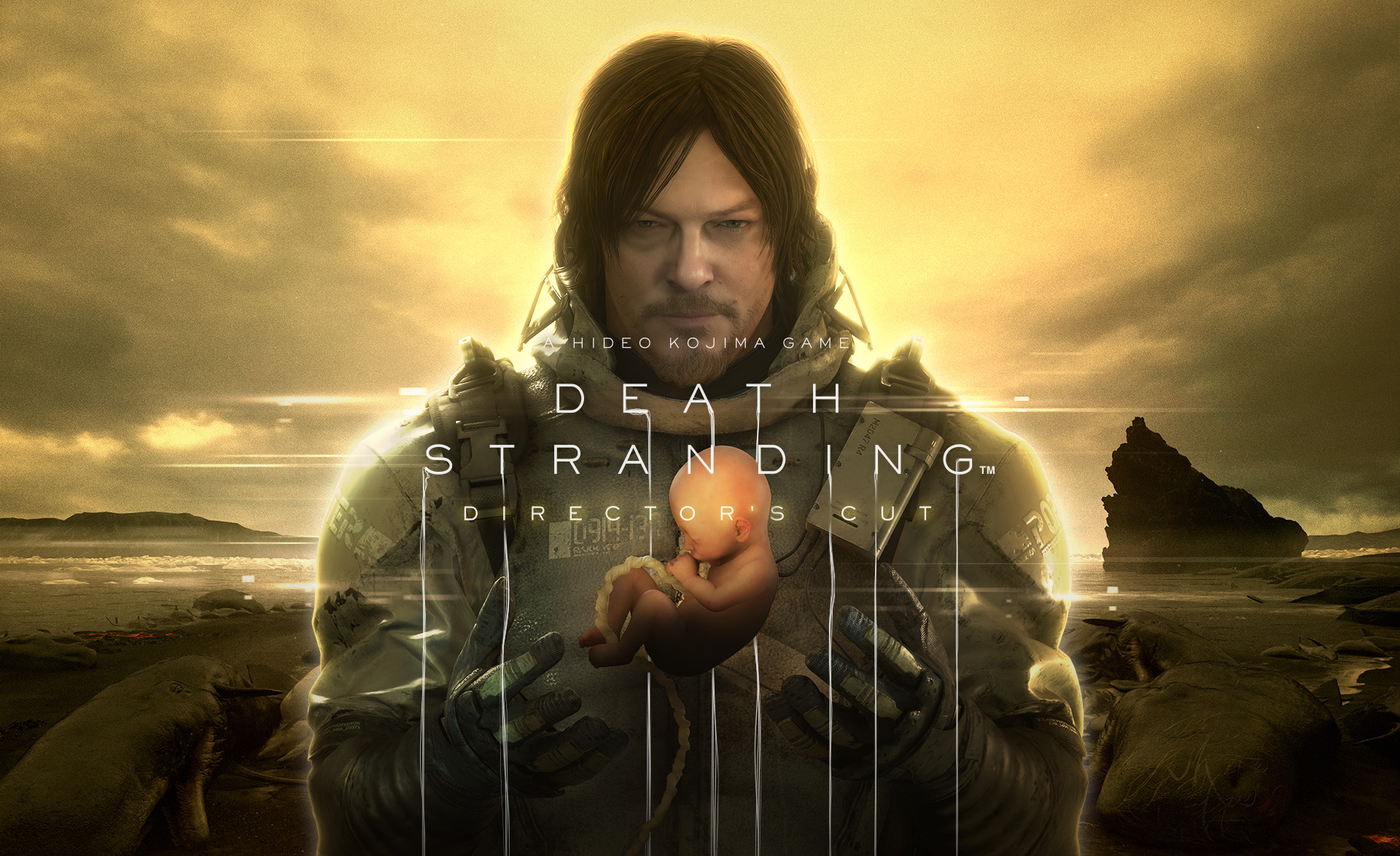

I’ve always found it difficult to describe one of my favourite games, Death Stranding. It’s a game that I fell head-over-heels for about five or six years ago on my PlayStation 4. Some people call it a ‘walking simulator,’ and while I suppose that’s technically true, it feels so much more profound than that. The game casts you as Sam, a post-apocalyptic postman in a mysteriously dying world. Your job, put simply, is to traverse what remains of the USA, connecting people who have been left behind onto a network.

At its core, Death Stranding is a story about making connections in a world where that’s incredibly hard to do. You never see any other players, but their structures—bridges, ladders, even charging stations—can appear in your world, and yours in theirs. You can show appreciation for their help with a simple ‘like.’ The game is unconventional, to say the least, and for years, I struggled to articulate why I loved it so much. It’s only since my autism diagnosis that I’ve begun to understand its deep appeal. It’s a game, I’ve realised, that mirrors many of my own autistic traits.

A Quiet Solitude in a Connected World

The gameplay experience in Death Stranding is profoundly solitary. You are, for the most part, alone, navigating a vast and beautiful landscape. Any social interaction is limited, both within the story and in its unique multiplayer element. For me, this has a familiar ring to it. My own social interactions sometimes feel awkward or limited, a trait many autistic people experience. The game captures this beautifully, creating an environment where connection happens at a distance—a supportive echo rather than a loud, chaotic conversation. The social difficulties many of us navigate are reflected here, but in a way that feels comfortable and affirming, not isolating. It’s a game about making connections without the overwhelming pressure of constant face-to-face socialising.

The Comforting Rhythm of Repetition

The gameplay loop of Death Stranding is, by any standard, very repetitive. You take on a delivery, find the packages, and then deliver them. You build structures to help you get across the land—a bridge here, a zip-line there. Occasionally, there are cutscenes that advance the story, but then you’re right back to it. Rinse and repeat. This regularity is incredibly comforting and pleasing to me. As an autistic person who finds solace in routine, this rhythmic, predictable structure is a delight. It allows me to get into a flow state, knowing exactly what is expected of me and what the next step will be. There’s a deep, calming pleasure in that predictability.

Hyperfocus and the Monotropic Mind

Sam, the main character, is defined by his single-minded focus on the task at hand. He’s a man with a job to do, and he does it with unwavering determination. This trait strongly reminds me of those moments when I’ve been in the flow, deeply engaged in a special interest. The scientific concept here is called monotropism, which describes the tendency for autistic people to have a deep, focused attention on one or a few interests at a time, making it hard to shift that focus. When I’m in the midst of a delivery, plotting my route across the treacherous terrain or building a new structure, I’m completely engrossed. Sam’s focus isn’t just a character quirk; it’s a window into the hyperfocused, monotropic mind, and it’s a theme that I, and I’m sure many other neurodivergent players, find deeply resonant.

This year, when Death Stranding 2: On the Beach launched, I dived right back into that world. It’s been just as appealing as the first game. All the essentials remain, but with some lovely enhancements. Truth be told, I’ve been playing it fairly obsessively since it launched… and I have no plans to stop.

The Illumination of Seeing Yourself Reflected

The most powerful takeaway for me isn’t a practical tip or a strategy for the game, but the simple, profound comfort of seeing myself reflected in the game I’m playing. Whether it was intentional or not—and I have a sneaking suspicion it was—Hideo Kojima, the game’s creator, has crafted an experience that speaks directly to the autistic experience.

And seeing yourself represented is so important, isn’t it? As a gay man, I know this feeling. I know how affirming it is to see a part of your identity reflected honestly and respectfully in media. I know it’s important for my two dual-heritage children to see themselves in the world around them. And now, I appreciate it on a new level as someone who is neurodivergent. To find that reflection in something as unexpected as a video game about a post-apocalyptic postman is truly special.

Leave a Reply